Pdcaas Score for Combined Vegetarian Diet

There is an on-going controversy that pits plant-based protein against animal-based protein advocates. The debate is on how to label plant-based alternatives to animal-based foods. Examples of such foods range from "vegan fish sticks" to "cashew milk" among many others.

Arguments from supporters of plant-based protein products say that consumers are better informed if the name of the traditional animal product is part of the plant food product's name. Consumers have a better understanding of how and where the plant products can be used. Also, if a new terminology is to be required for these foods, it will stifle innovation in a product category that is more sustainable and that offers health benefits over their animal counterparts.

Countering arguments by supporters of animal-based foods and beverages point out that in the U.S., the FDA and FSIS (USDA) have "Standards of Identity" for many of these foods.1 For example, "Milk is the lacteal secretion…obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows."2 Consumers have certain expectation when such regulated terms are used.

Such expectations involve health issues as well. Many proteins illicit allergenic responses. Would a consumer with an allergy—whether to milk or peanuts—easily understand the risks associated with a "peanut milk." And, there are concerns over the nutritional quality of such products. One tactic addressing the latter is to improve a plant product's nutritional quality by blending proteins.

Protein and nutrition

Although protein deficiency in the U.S. and other developed countries is rare, the shift to plant-based diets may have implication for some. Such groups include athletes endeavoring to be vegan and vulnerable populations. Protein requirements vary by life stage with the greatest need occurring during growth and development. The elderly are also be a concern. Protein food intake tends to decline in adults older than 71. Only about 30 percent of women and 50 percent of men meet the recommended intake level of protein foods.3

What can food manufacturers do to ensure their plant-based foods have the expected protein nutritional quality?

In the development of packaged processed foods, the question becomes, what are the steps that food manufacturers can take to ensure their plant-based foods have the protein nutritional quality expected and even needed by consumers?

Various methods are used to determine the nutritional quality of proteins. They include Net Protein Utilization (NPU) and Biological Value (BV). Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) is currently used by Canada4 for food labeling purposes and was in the U.S. as well until the 1990s when Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) became the preferred method. The WHO/FAO also currently uses PDCAAS.

PDCAAS values of proteins are also highly important for marketing reasons. While grams of protein per serving can be displayed on Nutrition Facts Panel, PDCAAS values must be used in the calculations of a product's Percent Daily Values (%DV). For a food to make protein claims such as "a good source of protein," the %DV must be shown on the label at certain levels, depending on the claim made.

The PDCAAS of a protein or food is calculated by multiplying its amino score by a digestibility factor. The amino acid score in turn is obtained by comparing the concentration of the "first limiting essential amino acid with the concentration of that amino acid in a reference (scoring) pattern. This scoring pattern is derived from the essential amino acid requirements of the preschool-age child."5

A high PDCAAS value is thus based, in part, on having an optimal amino acid profile. The human body cannot synthesize nine amino acids that are called essential or indispensable. These amino acids are used by the body in different proportions. Most animal-based foods provide these amino acids in about the proportions needed, but plant-based foods tend to provide proteins with less optimal amino acid profiles.6

Blended proteins and plant-based milks & meats

Limiting amino acid (LAA) scores as well as lysine scores for selected foods were given in an influential paper by Vernon Young and Peter Pellet published in 1994 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.7

Lysine is the LAA in many cereals. Lysine scores for brown rice, corn, durum wheat and sorghum were given as 66, 49, 38 and 35 respectively. Young and Pellet reported a broad range for the lysine content of nuts and seeds. While lysine is the LAA in peanuts (with a lysine score of 62) as well as almonds (58) and walnuts (47), pistachios and pumpkin seeds have a high lysine score at 107 and 129 respectively.

On the other hand, legumes such as beans (e.g., white, kidney, lima and wing) as well as chick peas, lentils, soybeans and mungbeans all had high lysine scores ranging from 115 to 120. Methionine is instead a limiting amino acid for some.

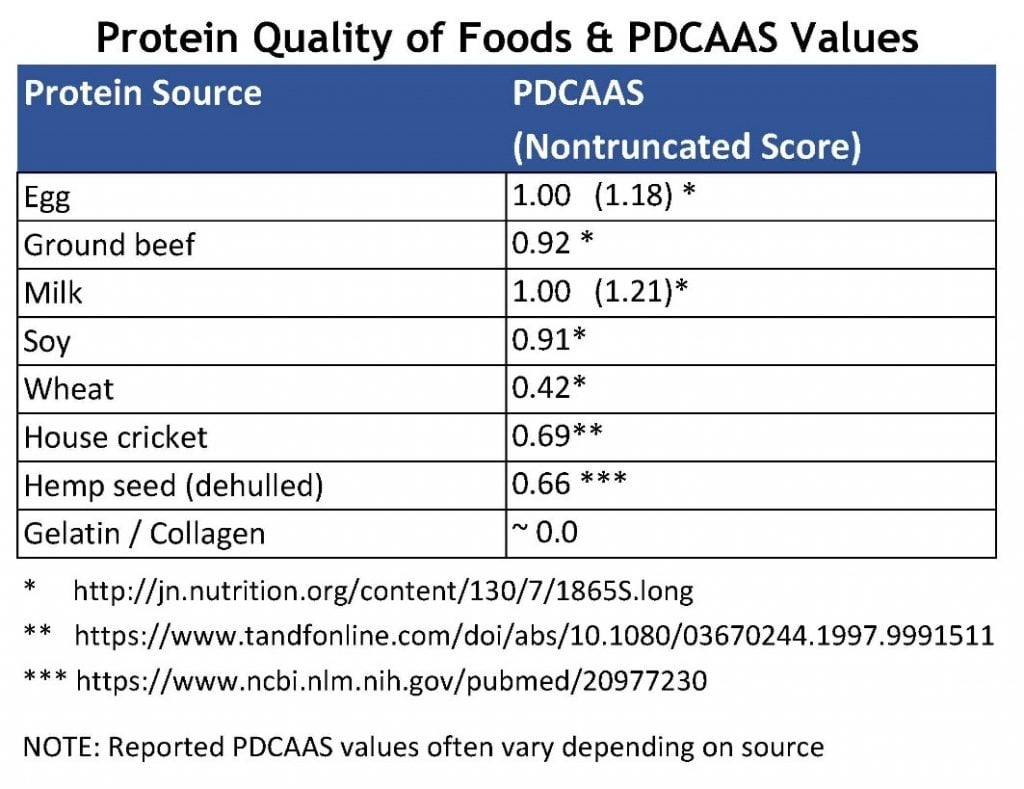

As for animal proteins, although dairy-based proteins, eggs and beef fare well (see section below on DIAAS), gelatin and collagen lack tryptophan and have a PDCAAS of essentially zero. Combining gelatin in foods along with high tryptophan proteins such as dehydrated egg whites or spirulina could remarkedly improve the product's PDCAAS.

Of course, few, if any, proteins are consumed in isolation for any length of time. Many to most of the nutritional community has concluded that by consuming a variety of plant materials in a day, all the essential amino acids needed for health can be obtained.8

However, consumers may hold food manufacturers accountable if they find a plant-based milk, cheese or vegan fish stick fed to their growing family provides less protein than the comparable traditional food. As a start, understanding PDCAAS values and the amino acid profiles of proteins is of value. These can be obtained through laboratory analysis or databases at private commercial labs to the USDA.9

A final note on protein quality and DIAAS

Although the WHO/FAO currently uses PDCAAS, the FAO has proposed replacing PDCAAS with the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIASS).10

Some in the dairy industry have championed DIAAS in that calculated PDCAAS values are truncated at 1.0 while DIAAS values are not, which can put dairy proteins at an advantage. See chart.

In a study by Rutherfurd SM, et al. published in 2015 in The Journal of Nutrition11, the PDCAAS and DIAAS of 14 proteins were calculated. At the high end, their MPC (milk protein concentrate), WPI (whey protein isolate), WPC (whey protein concentrate) and two SPI (soy protein isolates) had DIAAS values of 1.18, 1.09, 0.973, 0.906 and 0.898 respectively. In contrast, all had PDCAAS values of 1.00 except the second SPI at 0.979.

The study's conclusion noted that "Untruncated PDCAAS values were generally higher than DIAAS values, especially for the poorer quality proteins; therefore, the reported differences in the scores are of potential practical importance for populations in which dietary protein intake may be marginal."11

References

- North Dakota State University Food Law: Standard of Identity, Petitions, Food Additives, Food Product Claims, and Organic Food

- CFR Title 21, Section 131: Milk and Cream

- 2017 Presentation by Joanne Slavin, PhD: Proteins for Health: Issues, Updates and Opportunities [PDF]

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency: Protein

- Schaafsma G. The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score.J Nutr. 2000;130(7):1865S–1867S.

- Jeter J. Woolf, PJ, et. al. vProtein: Identifying Optimal Amino Acid Complements from Plant-Based Foods. PLoS One. 2011; 6(4): e18836.

- VR Young and PL Pellett. Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59(suppl): l203S- l2S [PDF]

- Craig, WJ; Mangels, AR. "Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets" (PDF). Journal of the American Dietetic Association. July 2009. 109 (7): 1267–1268 [PDF]

- USDA Nutrient Data Laboratory. https://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/usda-nutrient-data-laboratory (Accessed November 3, 2018)

- Report of an FAO Expert Consultation: Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition Food and Nutrition Paper 92 [PDF]

- Rutherfurd SM, et al. 2015. J Nutr. 45(2):372-9. Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Scores and Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Scores Differentially Describe Protein Quality in Growing Male Rats

The views, opinions and technical analyses presented here are those of the author or advertiser, and are not necessarily those of ULProspector.com or UL. The appearance of this content in the UL Prospector Knowledge Center does not constitute an endorsement by UL or its affiliates.

All content is subject to copyright and may not be reproduced without prior authorization from UL or the content author. The content has been made available for informational and educational purposes only. While the editors of this site may verify the accuracy of its content from time to time, we assume no responsibility for errors made by the author, editorial staff or any other contributor.

UL does not make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy, applicability, fitness or completeness of the content. UL does not warrant the performance, effectiveness or applicability of sites listed or linked to in any content.

Pdcaas Score for Combined Vegetarian Diet

Source: https://knowledge.ulprospector.com/9110/fbn-blending-plant-proteins-for-more-nutritional-processed-foods/